Education and Resilience in Kyiv

Under siege, the Kyiv School of Economics has managed to expand, track Russia’s war debt, and build bomb shelters for schoolchildren. Two University of Chicago professors witnessed that resilience while teaching there this year.

Konstantin Sonin, the John Dewey Distinguished Service Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy, and Scott Gehlbach, the Elise and Jack Lipsey Professor in the Department of Political Science, the Harris School of Public Policy, and the College, have longstanding personal connections to faculty and administrators at the Kyiv School of Economics. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, and the city nearly fell into Russian hands, the two colleagues wanted to help the school in whatever way they could.

It turned out one of the best ways was for them to be present.

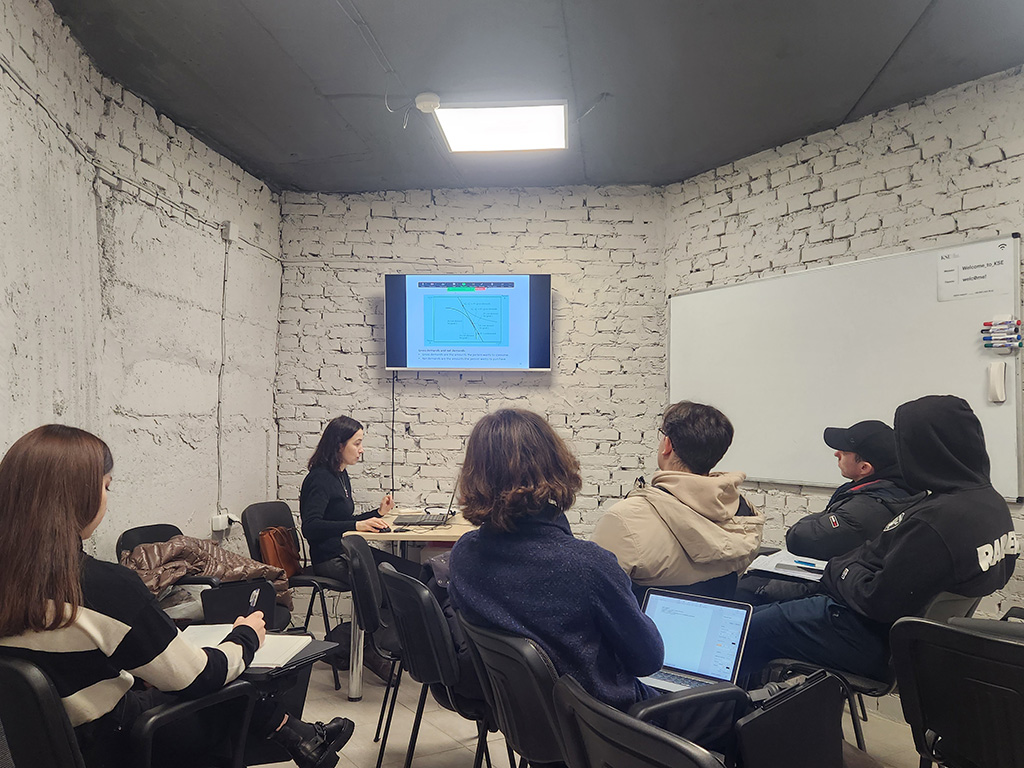

This year, Gehlbach and Sonin traveled to Kyiv and taught in an extraordinary atmosphere. Sonin led classes that were interrupted by air raid sirens only to resume minutes later in bomb shelters. They witnessed a university under siege that managed to raise $70 million since the start of the war to support education (including classroom shelters for schoolchildren), defense, and humanitarian relief. They spoke with students and professors quantifying the war’s impact for reparations and advising Ukraine’s government on how to keep the economy growing during the war.

“It is completely inspirational,” Gehlbach recalled. “The school has not only survived. It’s expanded since the beginning of the war. The people who work there are working 24 hours a day, seven days a week on very little sleep, and with incredible energy, keeping this institution going and moving forward. I just have nothing but admiration for them.”

Ukrainians are prioritizing education during the war, Sonin said, to preserve human capital in the face of physical damage being inflicted. Many schools at all educational levels have built bomb shelters or converted basements to classrooms, he said.

“They’re doing an amazing job keeping the educational system going,” Sonin said.

Air raids and Luke Skywalker

The two professors taught at the school, known by the acronym KSE, six months apart.

Sonin, who serves on KSE’s international academic board, arrived in March 2023 and stayed for two weeks. He taught classes on macroeconomics and the history of economic thought. He also lectured at a prestigious mathematics high school.

Gehlbach, whose research focuses on the contemporary and historical experience of Russia and Ukraine, has visited Ukraine about a half dozen times since 1996. On his trip in late August and early September, Gehlbach lectured on wartime damage and recovery--citing the experience of post-war Japan--and Ukraine’s oligarchy.

Air raid sirens interrupted classes more than once. Before one of his lectures, Gehlbach heard the sirens and spent about three hours in a hotel basement converted to a bomb shelter. Two were killed before the danger cleared about 5 a.m. During a second air raid, it was an hour spent in the bomb shelter.

“I remember people looked a little bleary eyed the next morning at school,” he said, “but we were really struck by how many people were there, notwithstanding the fact that this air raid had occurred hours earlier.”

Forged through collective trauma and perhaps with no acceptable choices but to carry on, KSE faculty, administrators, staff, and students demonstrated astonishing resilience. Sometimes that capacity manifested itself in the students’ focus and ability to engage with the course material in the face of unnerving interruptions.

As an example, Gehlbach recalled sharing in one class that Japanese cities had bounced back after World War II. One student noted that Japan is an island nation. Ukraine always will border Russia, he told Gehlbach, which may inhibit cities along those borders from recovering population.

“I think it’s one of the most intellectually exciting, vibrant places that I’ve been to,” Gehlbach added. “People are very interested in learning social science for the sake of understanding the future of their country. There’s a relevance to what people are studying that is immediate.”

Harrowing as the air raid warnings could be, Ukrainians managed to inject levity into those moments, Gehlbach and Sonin recalled. An app that sent air raid alerts to mobile phones used the voice of actor Mark Hamill as Star Wars character Luke Skywalker.

“Attention. Air raid alert. Proceed to the nearest shelter,” the actor said, notifying users of an impending raid. “Don’t be careless. Your overconfidence is your weakness.”

When the raid ended, the app would play Hamill saying, “The air alert is over. May the force be with you.”

Despite the air raids, Gehlbach and Sonin said they felt safe.

“I was in the basements,” Gehlbach recalled, “and Ukraine's air defense systems shot down virtually all the missiles.”

Although Sonin experienced several air raid warnings, Russian attacks failed to materialize.

Born, raised, and educated in Russia, Sonin said the most difficult part of his visit to Kyiv were his feelings of guilt. Residing in Moscow in 2021-22, he opposed the invasion, worked to prevent it, and left the country shortly after the war started.

As a result of his efforts, Sonin has been placed on Russia’s federal wanted list on allegations that he disseminated false information about the Russian military. What he actually did was post social media reports about the killings of civilians in Bucha and the destruction of a theater in Mariupol.

“My country did this,” he said of the destruction in Ukraine, “but also, I wasn’t able to stop it.”

‘Incredible sense of common identity’

More than a dozen alumni of the Kyiv School of Economics have been killed since the start of the war, Sonin said. At dinner one night during his visit, a woman told Gelbach that everyone in Ukraine knows at least three people who have been killed along the front lines of the conflict.

That trauma and the frequent air raid sirens have become part of life in Kyiv, the professors said. Gehlbach recalled speaking with a man who lives in a high-rise apartment and is unable to get to the basement shelter every time the sirens sound.

“He told me that when he hears the alert, the first thing he does is hug his son and they go to the corridor, away from the windows,” Gehlbach said. “Then he listens for the sound of explosions and from that he judges how far away it is, which tells him if he and his son should go to the basement or not.”

Both professors said they are optimistic about the future of the Kyiv School of Economics and higher education in Ukraine.

Sonin said the city and nation are a cradle of European civilization—in science, education, and the arts. The invasion has fueled a robust national identity for Ukrainians, he added. After the war, the country will shed its Russian imperial and Soviet past.

Gehlbach said he witnessed “an incredible sense of common identity and common purpose.” Those bonds may be complicated after the war by a return to Ukraine’s historically troubled political environment, he added.

“I think that’s inevitable,” Gehlbach said, “and not necessarily a bad thing.”

Sonin said the war will bring the collapse of Vladimir Putin’s regime, Ukraine’s liberation of its territories and membership in NATO and the European Union.

“And this will be the best way to make sure that this is the last war in Ukraine,” Sonin said.

Gehlbach said he is most concerned about whether the U.S. and Europe continue to support Ukraine.

“Ukraine will fight regardless of what the West will do,” Gehlbach said. “What’s happened in parts of Ukraine has been so horrific that it creates incredible motivation to finish the fight. I just hope that the West is there to help Ukraine to the end.”

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO